For reasons that I can’t always articulate, Rachel Getting Married is heavenly to me. So imperfect that it’s perfect. So brutal that it’s beautiful…These are just a few of the conflicting phrases that come to mind when I watch this movie. I’d like to think that any complaint you might have about the film, I could find a reason to say: “Yeah, but THAT’S what’s so great about it!” Try me.

I watched it for the umpteenth time with my mother one night. The film deals with – to say the least – family troubles, so I thought she would appreciate it, or at least find it moving. Though she sat through the movie patiently, her final thoughts were: “It was just…weird. It made me uncomfortable.”

And really, that’s what’s so great about it. It’s uncomfortable. It’s so honest and anti-what-we-think-a-movie-should-be that it makes us uncomfortable. A majority of the people I know described the first thirty minutes as “slow…and weird…not a lot happens.” This is also (see, I told you I could do it) another reason why it’s great. Director Jonathan Demme takes the audience completely out of its element by making it feel as though you’re not even watching a movie, but rather, you’re watching all of these lives take place. And they’re laid out just as they are – all the fighting, the ugliness, the lack of communication, the resentment, and everything else that most families don’t want you to see. (Because that would be…uncomfortable.)

I read that Demme confessed somewhere that Rachel Getting Married was filmed with Dogme 95 in mind. For those who don’t know, Dogme 95 is – in short – a film movement initiated by Danish filmmakers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg in 1995, with the intentions of stripping films of their “Hollywood.” (You can read the official rules here.)

By its very nature, filmmaking is a deceptive and artificial process. And I don’t even mean in terms of story or characters – just the basics: lighting, sound, special effects, etc. These are some of the very things that von Trier and Vinterberg wanted to eliminate with the Dogme 95 movement. And why? To focus on one thing only: the story.

Thus, if you watch accredited Dogme 95 works, you’ll see that they’re very raw-looking. Jerky camera movements because it’s all hand-held, and no special lighting or fancy effects. But you can say one thing about them (or, most of them, since I’m personally not a fan of whatever “Julien Donkey Boy” is, for instance): You’re completely involved in the story and its characters.

Rachel Getting Married reminds me of an upscale Dogme 95 movie. They have a better camera, awesome set design and locations, and more well-known and acclaimed actors. But that doesn’t mean the essence of Dogme 95’s honesty isn’t there. There’s not much artificial lighting, most of it (if not all) appears to be hand-held camera, and overall the main focus is on the story and the characters. Not much else.

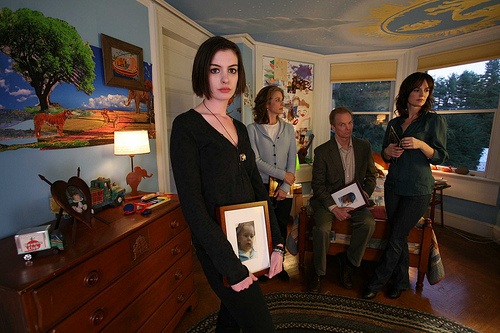

And both the story and the characters are heartbreaking, imperfect, conflicting, and contradictory. But they’re real. My favorite scene in Rachel Getting Married is when Anne Hathaway’s character, Kym, is spilling her guts out to her family. Kym made a horrible mistake that tore her family apart a few years ago, and she can’t seem to make anything right, or apologize enough. She asks, “Who do I have to be now?” This quote keeps popping into my head as I write this. Because what does film have to be now? What more can it be?

I believe we’re at a place in film where everything has been done. So many limits in technology, effects, and plots have been breached that maybe we can’t take it anymore. We still want creativity and entertainment, but maybe we want those things on smaller scales and budgets, and within realms that we recognize as our own. Maybe we want movies that don’t feel like movies, but like real life instead.

The mainstream public might not have noticed it ten years ago, but I think the Dogme 95 creators were really on to something here.